|

SEPTEMBER 27, 1999 VOL. 154 NO. 12

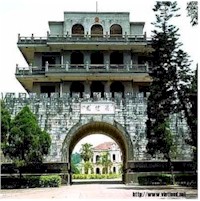

PINGXIANG: Border War, 1979

A

Nervous

- China Invades Vietnam

By TERRY McCARTHY

Early in the morning of Feb. 17, 1979, Chinese artillery batteries and multiple

rocket launchers opened fire all along the Vietnamese border with protracted

barrages that shook the earth for miles around. Then 85,000 troops surged

across the frontier in human-wave attacks like those China had used in Korea

nearly three decades before. They were decimated: the well-dug-in Vietnamese

cut down the Chinese troops with machine guns, while mines and booby traps did

the rest.

- Horrified by their losses, the Chinese

quickly replaced the general in charge of the invasion that was meant, in

Beijing's words, "to teach Vietnam a lesson," and concentrated their

attack on neighboring provincial capitals. Using tanks and artillery, they

quickly overran most of the desired towns: by March 5, after fierce

house-to-house fighting, they captured the last one, Lang Son, across the

border from Pingxiang. Then they began their withdrawal, proclaiming victory

over the "Cubans of the Orient," as Chinese propaganda had dubbed

them. By China's own estimate, some 20,000 soldiers and civilians from both

sides died in the 17-day war.

Who learned the bigger lesson? The invasion demonstrated a contradiction that

has forever bedeviled China's military and political leaders: good strategy,

bad tactics. The decision to send what amounted to nearly 250,000 troops into

Vietnam had been taken seven months before and was well-telegraphed to those

who cared to listen. When Deng Xiaoping went to Washington in January 1979 to

cement the normalization of China's relations with the United States, he told

President Jimmy Carter in a private meeting what China was about to do--and

why. Not only did Beijing feel Vietnam was acting ungratefully after all the

assistance it had received during its war against the U.S., but in 1978 Hanoi

had begun expelling Vietnamese of Chinese descent. Worst of all--it was cozying

up to Moscow.

In November 1978 Vietnam signed a treaty of friendship and cooperation with the

Soviet Union. A month later the Vietnamese invaded Cambodia, a Chinese ally.

Although Hanoi said it was forced to do so to stop Pol Pot's genocide and to

put an end to his cross-border attacks against Vietnam, Deng saw it as a

calculated move by Moscow to use its allies to encircle China from the south.

Soviet "adventurism" in Southeast Asia had to be stopped, Deng said,

and he was calculating (correctly, it turned out) that Moscow would not intervene

in a limited border war between China and Vietnam. Carter's National Security

Adviser, Zbigniew Brzezinski, said Deng's explanation to Carter of his invasion

plans, with its calculated defiance of the Soviets, was the "single most

impressive demonstration of raw power politics" that he had ever seen.

At the time Deng was consolidating his position as unchallenged leader of

China. Having successfully negotiated normalization of relations with

Washington, he wanted to send a strong signal to Moscow against further

advances in Asia. He also thought the Carter Administration was being too soft

on the Soviets, although he did not say as much to his American hosts.

Hanoi, for its part, was unfazed by Deng's demonstration of "raw

power." The Vietnamese fought the Chinese with local militia, not

bothering to send in any of the regular army divisions that were then taken up

with the occupation of Cambodia. Indeed, Hanoi showed no sign of withdrawing

those troops, despite Chinese demands that they do so: the subsequent guerrilla

war in Cambodia would bog down Vietnam's soldiers and bedevil its foreign

relations for more than a decade.

The towns captured by the Chinese were all just across the border; it is not

clear whether China could have pushed much farther south. Having lost so many

soldiers in taking the towns, the Chinese methodically blew up every building

they could before withdrawing. Journalist Nayan Chanda, who visited the area

shortly after the war, saw schools, hospitals, government buildings and houses

all reduced to rubble.-

- The war also showed China just how outdated its

battlefield tactics and weaponry were, prompting a major internal review of the

capabilities of the People's Liberation Army. The thrust for military

modernization continues to this day, even as the focus of China's generals has

shifted from Vietnam back to Taiwan--a pesky little irritant that could cause

Beijing even bigger problems if it decides to administer another

"lesson."

|